Tony Cardenas ’86, Salud Carbajal ’90 and Jared Huffman ’86 are making their mark.

By George Thurlow ’73

Congressman Tony Cardenas ’86 enters the U.S. House of Representative building in Washington, D.C.. Photo: Office of Tony Cardenas

Congressman Tony Cardenas’ Capitol Hill office in Washington, D.C., hangs a large powerful photo.

It is of Cardenas’ father, Andres Cardenas, and his wife’s grandfather, Cirico Quezada, picking potatoes in the dry dusty fields of Stockton in the 1950s. What is striking, besides the big potato bags hanging around their waists, are the broad smiles on both faces.

The image hangs where Cardenas, from his large office desk, can look at it every day. He is reminded, he recalled recently, that even when the work is hardest, you need to smile. A few steps away, in a glass covered coffee table, there are potato bags and a farmworker’s heavy belt on display.

“It reminds me that in just one generation, we went from picking potatoes to serving in Congress,” Cardenas said.

Throughout his political career Cardenas ’86, a mechanical engineering major at UC Santa Barbara, has never strayed far from UCSB. He loves to tell the story of how, when he chaired the Assembly budget committee in Sacramento, he became incensed at the slow pace of UC admissions offered to underrepresented minorities. In the budget language coming out of the Assembly, Cardenas wrote that UC was “failing California.” He threatened to withhold all of UC’s funding unless progress could be shown.

Then UC President Richard Atkinson was furious. He came to meet Cardenas but the meeting did not go well. Atkinson left “pissed,” recalled Cardenas, and did not know what to do. That was when UCSB Chancellor Henry Yang worked his political magic.

Yang made a point of bringing Cardenas a potted plant on his election to the Assembly. Cardenas later was helpful in getting funding for a new building on the UCSB campus. The two engineers developed a close relationship.

When Yang attended a Chancellor’s meeting with Atkinson where Atkinson expressed concern about the possible budget impacts of the Assemblymember’s action, Yang defended Cardenas. Atkinson said Yang should broker a deal.

Yang met with Cardenas and the two hammered out language that went to Atkinson and the Regents reinforcing existing programs aimed at boosting underrepresented enrollment. For his effort, UCSB received funding for a new psychology building, Cardenas observed.

Cardenas shares his remarkable trajectory with fellow Gaucho Congressman Salud Carbajal ’90, of Santa Barbara. Carbajal’s father and family came to the U.S. when Salud was just 5 years old. His father first worked in the copper mines of Arizona but moved to Oxnard to work in the fields.

Like Cardenas, Carbajal came to UCSB from a socio-economic background that hardly guaranteed success at one of the most Anglo campuses in the UC system.

At UCSB Carbajal, a Latin American Studies major, learned critical thinking skills that he uses to this day. He recalls taking a number of ethnic studies courses which opened up to him the diverse history of the United States and led him to appreciate his Latino roots.

“The Educational Opportunity Program was invaluable to me, “ he said. “It took a kid like myself and gave me an entire level of support to navigate this university world. I was the first in my family to attend college,” and like many first generation Gauchos, he had no family or social knowledge to lean on. “The support for me at UCSB was unbelievable. Lots of kids get the opportunity but there is a high failure rate.”

Like Cardenas, Carbajal has those roots on his wall. There is a picture of a grape picker surrounded by fruit box labels. On the opposite wall, there are photos of UCSB and commencement.

Midway through an interview with Coastlines in his Washington D.C. office, Carbajal receives a delegation from the Kurdish state of Kurdistan. He invites the reporter in on condition that the content of the meeting remain off-the-record. It can be shared that on this day Iraqi troops are amassing on the borders of Kurdish-held areas ready to crush the Kurdish republic. The Kurds have fought fiercely on the side of the U.S. in the battle against ISIS and the government of Syria. Yet the U.S. is backing the Iraqi government. The Kurds need help and Carbajal listens intently to their presentation. He notes that he is a first-year freshman in the minority party but pledges to go to Kurdistan before the end of the year to see the situation firsthand.

Salud Carbajal ’90 with troops outside Baghdad, Iraq, Christmas Day 2017. Photo: Office of Congressman Carbajal

His hands move with quick judo chops. “My nature is action,” he said. “But here you have to figure out how things work.”

Two days later, the Iraqis invade Kurd-held territories and ignite yet another civil war in Iraq. A year earlier Carbajal was dealing with Montecito water woes and county budget shortfalls. Now he is a player in the volatile and dangerous Middle East conflagration.

At least the conflagration is a world away.

For UC Santa Barbara’s third Congressman, Jared Huffman ’86, the inferno is right in his district. Three thousand homes have burned, more than 50 people, many of them elderly, unable to flee their homes are dead and 500 have been hurt.

Huffman stayed in his district as the fires burned. He turned his entire congressional staff into an army of “case workers” to take calls from constituents who need help.

In the middle of an interview with Coastlines just one week after the fire began, there is a knock at the front door. It is a neighbor delivering retail and food gift cards. A political fundraiser Huffman had planned in the district was turned into an “open to all” fundraiser for fire victims. The price of admission: a gift card for those impacted by the fires. The event raised $13,000 in gift cards and Huffman’s campaign was donating another $35,000. His neighbor was contributing more.

In his third term in Washington after several terms in Sacramento, Huffman says he learned at UCSB how to deflect the hard ones and power forward in the depths of defeat.

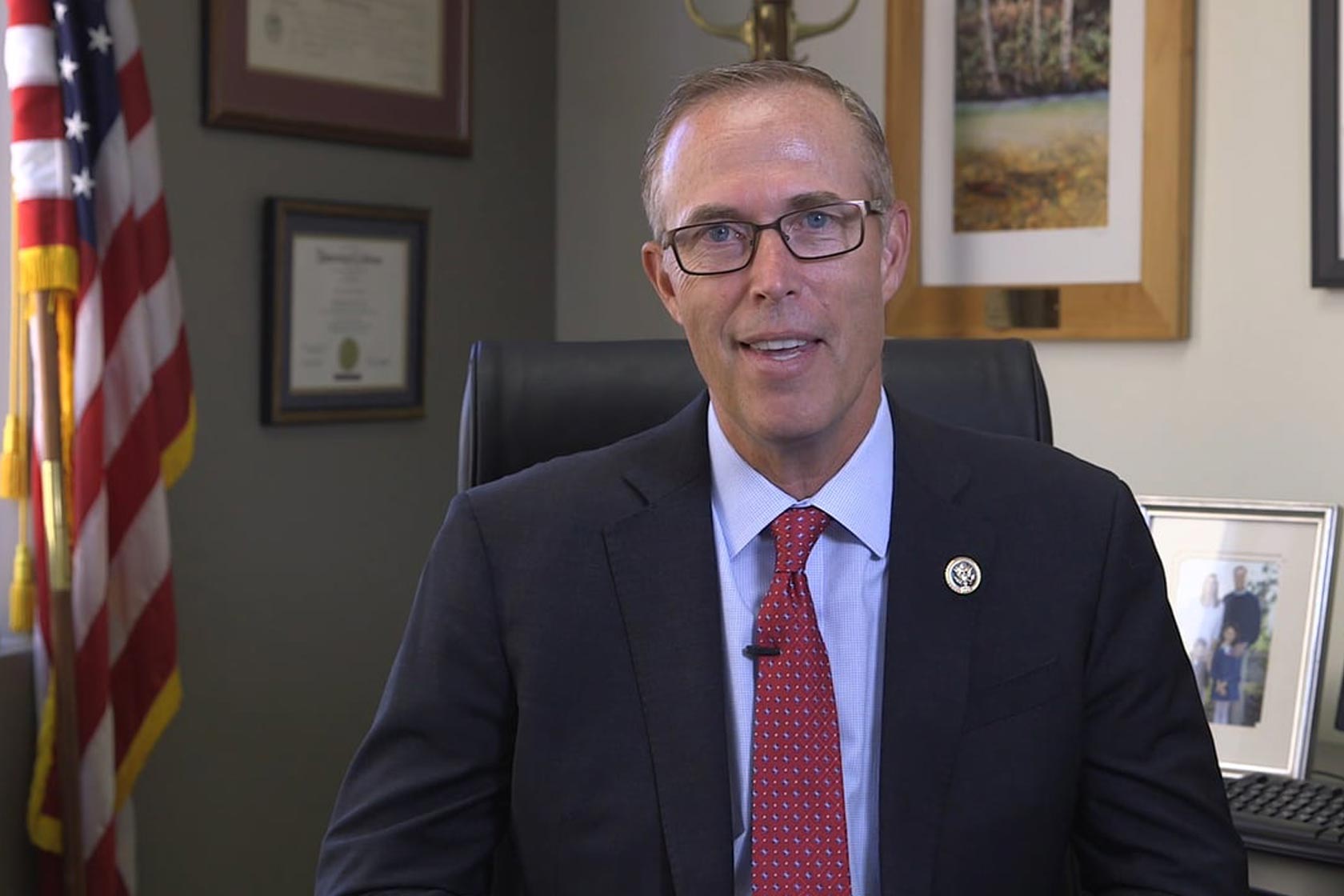

Jared Huffman ’86

Huffman came to UCSB from Independence, MO. on a volleyball scholarship. He was recruited by volleyball powerhouse UCLA but took one look at the UCSB campus and knew he wanted to be a Gaucho. He went on to play on the men’s USA Volleyball team that won a world championship. While his Washington, D.C. office walls contain a fair number of sports photos, the most striking art is of two Mad River salmon printed by taking salmon, applying ink and then rolling the fish across art paper. The effect is stunning.

“I was exposed to so much diversity, critical thinking and inspirational mentorship,” he recalled. It was on the UCSB campus, between the mountains and the ocean, that he developed a love for the outdoors and a respect for the environment. He obtained a law degree from Boston College and became an attorney for the National Resource Defense Council, a leading litigator of major environmental legal issues.

Today Huffman is the second ranking Democrat on the Natural Resources Committee. Because he is in the minority party, his work is mostly blocking rollbacks of environmental protections and standards, or “working around the edges” of legislation.

Huffman points out the dysfunction in Congress that he blames on a “majoritarian” system where the majority in the House of Representatives controls all hearings, debate, legislation and scheduling. The minority party is effectively blocked from participation, he observed. This is a sharp contrast to his days in Sacramento where as a committee chair he welcomed Republican amendments and debate. He felt it made the subsequent legislation stronger and less partisan. He expects Democrats to regain the majority and his goal is to return to the bipartisanship he saw in Sacramento. “I’m focused now on good government,” he said.

He points to Carbajal as an example of how there can be less partisanship. Carbajal’s staff remarked that when he passed a recent Republican caucus meeting with members spilling into the hallway, a number of them greeted him with warm smiles and handshakes.

“Salud is a consistently optimistic person,” Huffman observed. (The two are roommates in a Capitol Hill house. Carbajal has the smallest room because he is the most “frugal.” For his part Carbajal sets the standard for neatness and tidiness, showing his two Congressional roommates his Marine Corps bed-making ritual.)

That Marine background is what motivated Carbajal to seek a seat on the powerful House Armed Services Committee, a panel that controls 55 percent of the discretionary spending in the national budget. It is also, Carbajal asserted, one of the most bipartisan panels.

On that panel, Carbajal has pushed a strong defense effort while championing diversity, gender equality and climate change and its impact on national security.

He tells the story of how the Army had purchased body armor for women that was ergonomically shaped differently from men’s body armor. Carbajal learned that the Marine Corps was not going to follow suit, instead giving women different sizes of men’s body armor. “I’m a Marine,” said Carbajal, “but I took the Marine Corps to task” in a committee hearing. The Corps soon followed the Army’s lead.

Carbajal still feels the bias against Latinos, even as a congressman at a recent function handed him car keys, thinking he was the valet. “I don’t sweat the small stuff,” Carbajal said.